Can systems change if we don't talk about power?

Talking Doughnut Economics and Power Dynamics in London

Last month I co-hosted a workshop (with the brilliant Sara Mahdi) titled ‘How do power dynamics impact our ability to drive change?’ with London Doughnut Economy Coalition and as part of Global Donut Days. Global Donut Days is an opportunity for countries across the world to showcase and celebrate how they are applying the Doughnut Economics model to drive change. The aim is to inspire and connect local initiatives with a global network of change-makers.

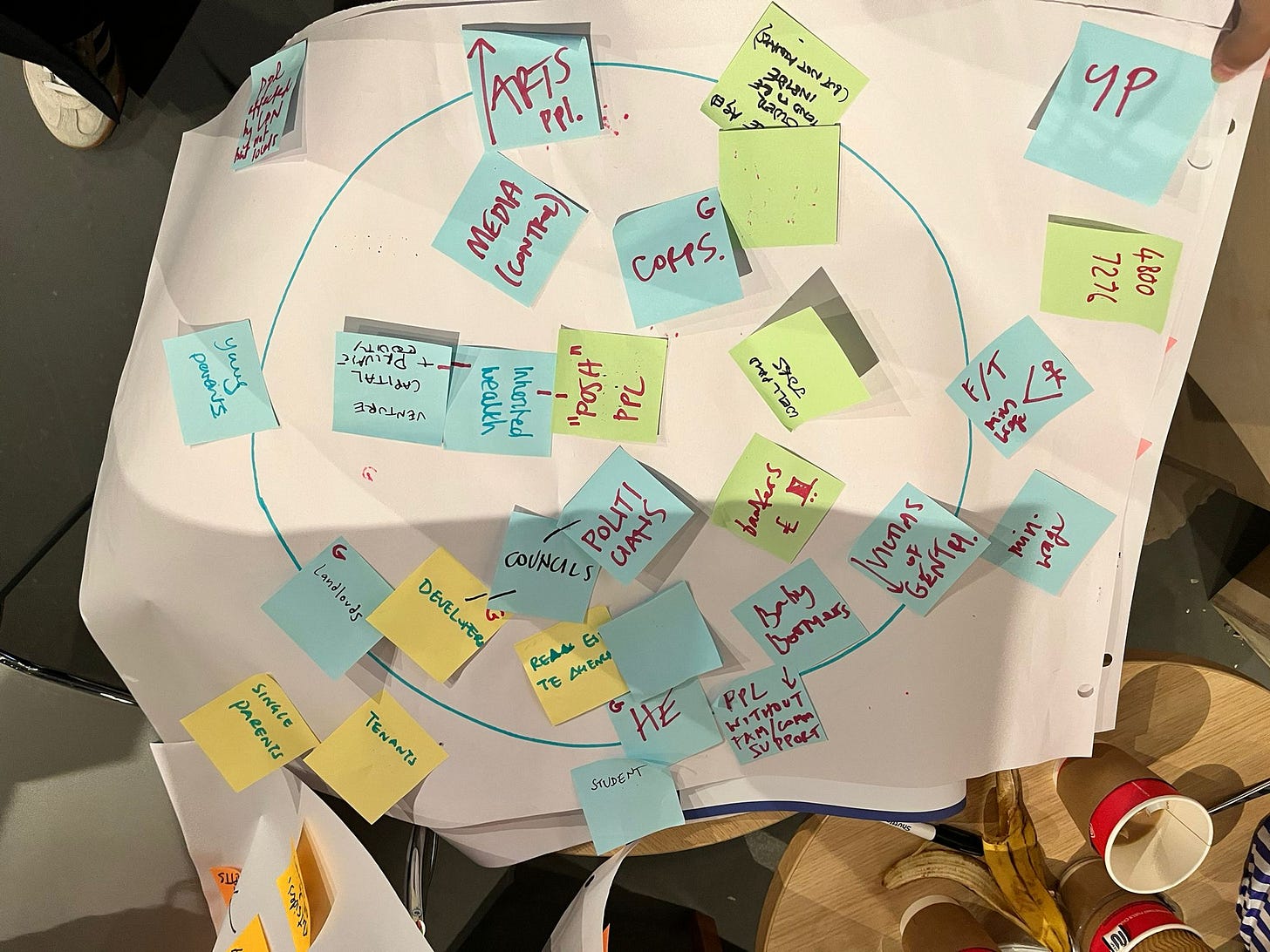

This session was two hours long and the first hour was an 'introduction to Doughnut Economics. We then had a very tight sixty minutes to dive into the deep topic of power dynamics in London. The session was aimed at young people (18-30) but there ended up being a mix of ages in the audience. In this article I’ve synthesised the information participants shared on their lived experiences of life navigating power imbalance in London.

What questions did we ask participants?

In order to tap into people’s lived experience, we focused on access to resource, space, governance and decision making. This was an ambitious list of questions we facilitated discussions on. We also sought to spark conversations around holding people in power accountable (i.e. question 8).

I personally thought question 3 was important because of how much I felt my circles changed over time. I grew up in Streatham, which has a large Afro-Caribbean community and this was very much reflected in my primary school experience. I learnt a lot about the culture, food, language etc. But from secondary school onwards, all the spaces I entered became a lot less diverse or a lot more segregated.

In a longer session, I’d focus a lot more on questions 3 and 8 before talking about access and feelings of welcome/unwelcome.

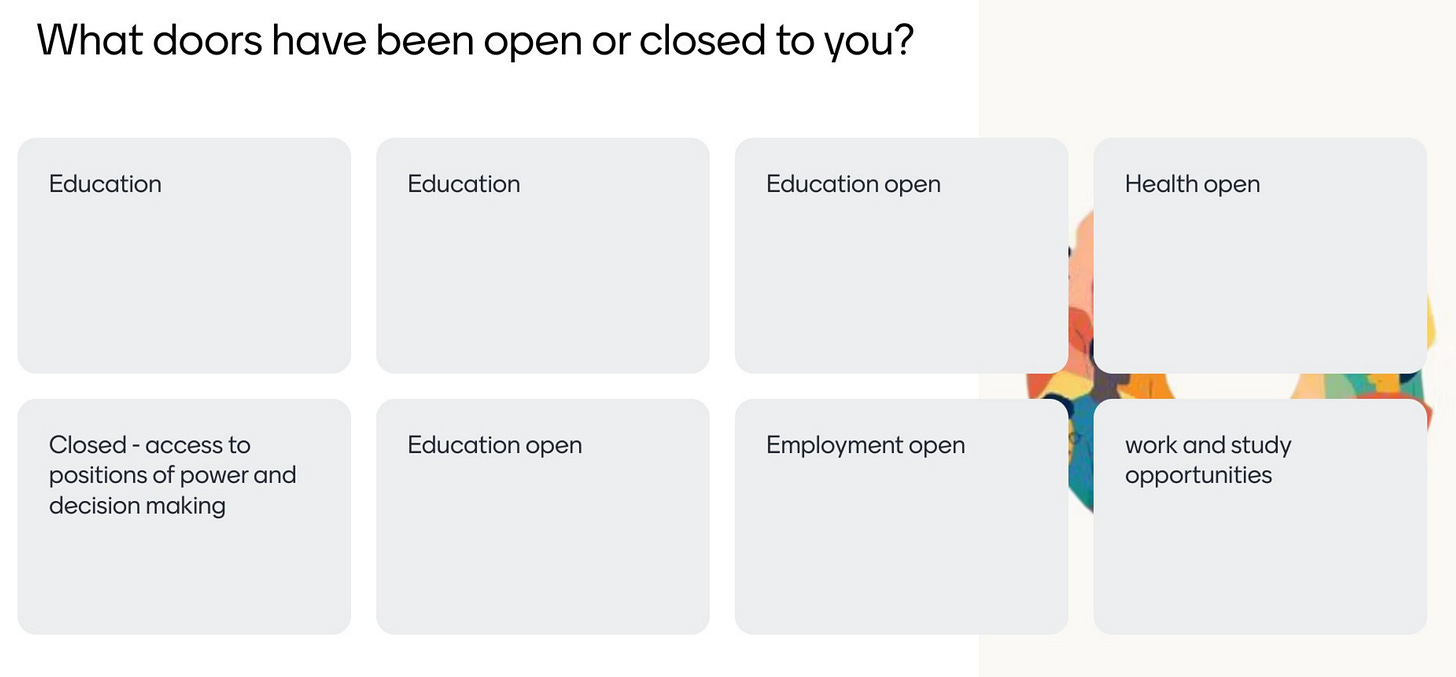

What doors have been open or closed to you?

What makes you feel welcome or unwelcome in different spaces?

What’s changed in your neighbourhood over time? Who’s benefited? Who lost out?

What spaces or opportunities feel easy for everyone to access?

Who has easy access to London’s resources and spaces?

Who’s not part of the conversation or benefits?

Who’s being pushed out of communities or spaces?

Who benefits from keeping others out or maintaining exclusion?

What was the objective of the session?

The ultimate objective of the session was to reframe the question ‘How can we make London a fairer, greener city within the Doughnut?’. Because how can we talk about making things fairer without talking about what people’s lived experience of unfairness looks like? I used the elephant metaphor from systems thinking to introduce the topic, adapted to include more explicit descriptions of how power dynamics impact lived experience.

I also introduced the concept of fractal thinking to encourage people to feel empowered to change a complex system, embedded with power imbalance.

Why do we need to talk about power?

“I open my own doors because i’m not a victim of White privilege.”

I wanted to start by discussing this response, which somebody anonymously submitted to the question ‘What doors have been open or closed to you?’. This is interesting because we didn’t use the term White privilege anywhere in the workshop. It’s also interesting because privilege isn’t something that one can be a victim of. This response could suggest several things:

This person might be pushing back against what they perceive as an over-focus on structural barriers

This person could be expressing frustration with discussions that they feel diminish individual agency

This person might be reacting to feeling defensive about discussions of privilege

These tensions around power and privilege emerge even in spaces dedicated to social justice and systemic change. In fact, they might surface more strongly precisely because these spaces aim to transform systems. When someone in a workshop about building a better economy for all responds defensively to perceived discussions of privilege - even when that term wasn't used - it tells us something important. It shows how these dynamics live not just 'out there' in obviously unequal spaces, but within our own movements and communities.

This is exactly why conversations about power and privilege are crucial in spaces like Global Doughnut Days. When we're working to reimagine economic systems and build a better world for all, we must be willing to examine how power dynamics play out in our own spaces and within ourselves. The discomfort, defensiveness, and desire to assert individual agency over structural analysis - these aren't barriers to the work, they are the work. Creating transformative change requires us to navigate these tensions with honesty and care, starting with our own communities.

What were key insights of the day?

Education Paradox: While education was consistently cited as "open" and simultaneously having opened doors for many people, this didn't translate into access to the jobs people really wanted or to positions of power.

Restricted Mobility: Despite London's openness in the form of freedom of movement (i.e. through public transport), many felt they couldn’t freely choose where to live. Some mentioned being priced out of their birth neighbourhoods, whilst others felt constrained by visa status or family responsibilities

Green Spaces as Common Ground: Green spaces emerged as the one type of space that nobody questioned as unwelcoming. But one participant's comment about safety reminds us that even in our most accessible spaces, power dynamics still play out. Whether this safety concern was about day or night or whether it was gender-specific matters - it points to different kinds of exclusion requiring different solutions.

Cultural Industry Gates: Employment in arts and cultural industries was specifically noted as closed, despite these being spaces that should celebrate diversity. This contradiction suggests particular barriers in sectors that often pride themselves on inclusivity. It raises questions about who gets to produce culture versus who gets to consume it.

Grassroots vs. Institutional: Grassroots-led community spaces feel more welcoming and accessible than official council-funded projects, suggesting something important about how institutional power affects welcome. One participant specifically contrasted their positive experiences with grassroots projects against struggles with funded "sustainability" projects. This points to a disconnect between institutional approaches to inclusion and what actually makes people feel welcome.

Open Services, Closed Opportunities: Basic services like healthcare and public transport feel accessible, but deeper engagement remains a struggle. While participants could access fundamental services, they faced barriers to preventative healthcare and community organising. This suggests a pattern where surface-level access exists but deeper participation is restricted.

Day vs. Night: While participants noted enjoying various spaces during the day, they specifically highlighted struggling to access these same spaces at night. What's notable is that this wasn't just about spaces being closed, but about safety and the quality of access - suggesting that even when spaces are technically 'open' at night, different dynamics come into play that affect who feels welcome.

Community vs. Commerce: While transport and safety have improved in neighbourhoods, rising rents and chain stores are eroding authentic community connections

Power Distance: There's a clear divide between those who can influence the city's development (through money or position) and those who must simply navigate the changes

Minimum Wage Margins: Living on minimum wage in London creates a constant calculation of access, where even 'public' spaces often have hidden costs of participation. Multiple participants noted how minimum wage workers are both excluded from the city's social and cultural life and from conversations about how to improve it. This creates a double exclusion where those most impacted by affordability barriers are least likely to be involved in decisions about making spaces more accessible.

Single Person Penalty: London's systems create specific barriers for those without combined household resources. Some participants noted being priced out of areas they could previously afford alone, others mentioned how single parenthood restricted job opportunities. Being able to share resources - whether through family wealth or partner income - has become almost prerequisite for full participation in city life.

People Make Places: It's often down to the people that make you feel like you belong somewhere - when there's a good mix of different people, people are open-minded and friendly, it just feels right. But when that's missing, even if there's nothing obviously stopping you from being there, it can still feel like you don't fit in.

Physical Barriers: A lot of places have features that make them feel less welcoming - like having to pay to get in, being watched by security cameras, or dealing with fences and barriers. Even if these aren't meant to keep people out, they create an atmosphere that feels more about control than welcome.

How can we make London…?

The final activity of the session asked people to finish the prompt:‘How can we make London…?’ by incorporating language and framings from the discussions. As it was the end of a long day and we’d crammed a lot into 60 minutes, the outputs didn’t feel as insightful as the discussions.

Nevertheless, I used the information gathered in Mentimeter as well as the posters to craft framings, which capture the nuanced experiences of people in London. The aim is not to have robust questions for redesign (though some could be used for this purpose), but to get people imagining about what changes to their experiences they’d really like to see. It’s difficult to imagine radically different realities to ones you already experience.

How can we make London a city where local shop owners have as much influence over their neighbourhood's development as property developers?

How can we reshape London's neighbourhoods so that renting doesn't mean feeling temporary in your community?

How can we make London a city where education connects communities and enables people to find work that they are passionate about?

How can we make London a city, where working minimum wage jobs doesn't mean constantly calculating if you can afford to belong?

How can we make London a city where the security of housing isn't determined by personal wealth or family inheritance?

How can we make London a city where nighttime spaces feel as welcoming and safe as daytime ones for all residents?

How can we make London a city where local food markets reflect neighbourhood cultures rather than development plans?

How can we make London a city where creative spaces have the same stability as commercial venues?

How can we make London a city where grassroots organisations have the same access to decision-making spaces as corporate stakeholders?

How can we make London a city where maintaining community connections is as valued as increasing property values?

These questions highlight specific power imbalances rather than using broad terms like 'fairness' or 'inclusion', and they reflect the concrete experiences shared in the workshop.

This is such important work, thanks for synthesising and sharing